The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #31: Rosie Schaap

"Writing about death and loss and grief in the midst of a pandemic added a pretty tough topcoat of sadness to the layers that were already in place."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

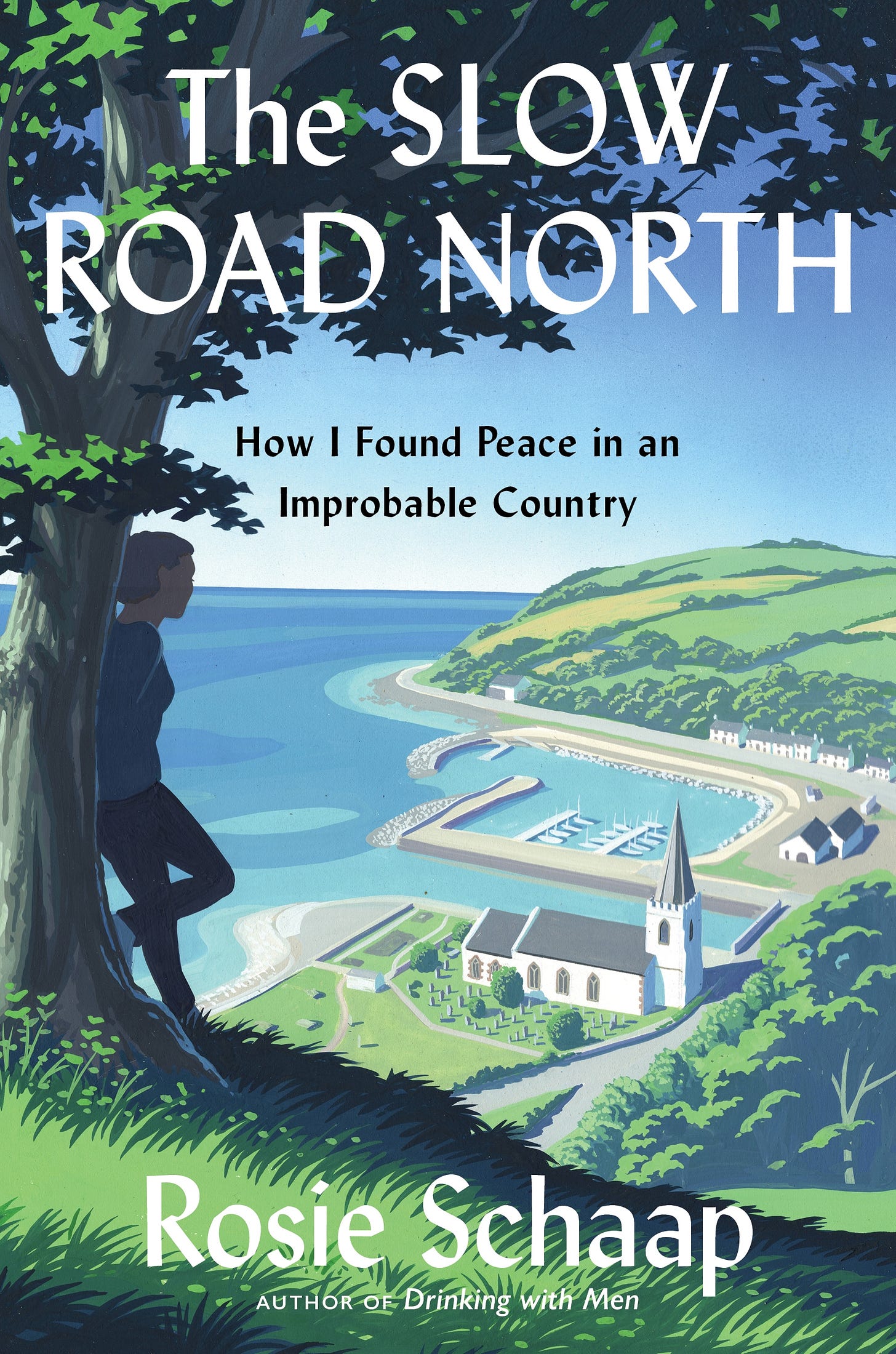

Here’s the thirty-first installment, featuring , author, most recently, of The Slow Road North: Finding Peace in an Improbably Country. -Sari Botton

Rosie Schaap is the author of Drinking with Men: A Memoir and Becoming a Sommelier. Her new book is The Slow Road North: How I Found Peace in an Improbable Country. She was a columnist for The New York Times Magazine from 2011 to 2017, and her personal essays have appeared in numerous anthologies. She was previously employed as a community organizer and a manager of homeless shelters. Born and raised in New York City, she has lived on Ireland’s Antrim Coast since 2019.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m 53. I wrote a poem in 1st grade about the color green. So that means I’ve been writing for about 47 years.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

The Slow Road North: How I Found Peace in an Improbable Country—August 20th, 2024.

What number book is this for you?

It’s number 3.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

It’s a memoir—but it also has a substantial social/oral history component. Much of it deals with my own grief following the deaths of my first husband and my mother a year apart. But it’s also about Glenarm, the small coastal village in Northern Ireland where I’ve lived since 2019, and tells the stories of some of my friends and neighbors here.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

In Northern Ireland—a region the rest of the world usually associates with sectarian violence—I paradoxically found a peaceful and beautiful place in which to confront my losses and learn how to live with my grief.

The Slow Road North is a memoir—but it also has a substantial social/oral history component. Much of it deals with my own grief following the deaths of my first husband and my mother a year apart. But it’s also about Glenarm, the small coastal village in Northern Ireland where I’ve lived since 2019, and tells the stories of some of my friends and neighbors here.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

From the time I was a kid and then all the way through college, I wanted to be a poet. But I learned pretty quickly after graduating that poetry was a hell of a tough way to make a living—and that I probably had neither the poetic talent nor the stamina to give it a go. But it was poetry that first led me to Ireland in 1991—I first came here for a summer, mostly to study Yeats, so my lifelong love for poetry played a part in my love for Ireland, a love that powerfully informs my new book.

After jobs in publishing, in nonprofits, in education, and even as a librarian at a parapsychology organization, I kind of backed into journalism (which, as the daughter of a journalist, I’d resisted for most of my life), and into creative nonfiction. In my 30s, I had an idea for a book I just knew I had to write (Drinking With Men: A Memoir, my first book). And in my 40s, after the deaths of my mother and my first husband, and several trips to Northern Ireland, the idea for The Slow Road North started to coalesce.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

I took a chance when I submitted a book proposal that included only one completed chapter and an explanation that I’d then have to move to Glenarm and write about my life here as it unfolded in real time. And I’m very lucky that Mariner Books was willing to take a chance on me. As for the hardest parts of writing the book: I don’t think it’s easy for anyone to write about the deaths of loved ones, and the grief that follows such loss. And writing about death and loss and grief in the midst of a pandemic added a pretty tough topcoat of sadness to the layers that were already in place.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

I think I made some mistakes handling my treatment of some real people in my first book: a couple things that seemed innocuous to me turned out to have been hurtful to others. Since then, I have approached writing about real people with deeper tenderness and, I hope, greater sensitivity. With the permission of the people I write about in The Slow Road North, I did not change names. I ran any passage that quoted or depicted the people I interviewed by them, and made the changes they requested. There are some references to people whom I did not interview, and I didn’t clear all of those by the people to whom I made reference—but I trust that my judgment in these cases was sound and sympathetic.

After jobs in publishing, in nonprofits, in education, and even as a librarian at a parapsychology organization, I kind of backed into journalism (which, as the daughter of a journalist, I’d resisted for most of my life), and into creative nonfiction. In my 30s, I had an idea for a book I just knew I had to write (Drinking With Men: A Memoir, my first book). And in my 40s, after the deaths of my mother and my first husband, and several trips to Northern Ireland, the idea for The Slow Road North started to coalesce.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

The folklorist Henry Glassie’s enormous and extraordinary 1982 book, Passing the Time in Ballymenone: Culture and History of an Ulster Community, was a tremendous inspiration.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

It is scary to put ourselves and our work out there. I think that’s true for all writers, but I don’t think it’s unfair to say that we memoirists have it extra hard—it’s not just our writing that is subject to criticism and scrutiny, it’s our lives. But if you have a book idea that’s keeping you awake and demanding that you sit down and write that book, and a sense that it will be entertaining, and otherwise of value, to readers, you really should sit down and write that book. As for the publishing process itself, it’s important to put yourself out there, too—go to readings and book signings, meet other writers, read their work. It was a writer I met at a reading who put the editor of my first book in touch with me.

What do you love about writing?

Those rare, blissful moments when I know it’s going well. That’s a real high for me.

What frustrates you about writing?

The majority of other moments when I feel like it’s not going well at all.

What about writing surprises you?

I used to fret a lot about structure, and then I started to relax and let the content determine the form. Watching the shape of an essay or book develop in this way is always surprising, and sometimes even thrilling.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

I used to be very much a morning writer, but since moving to Ireland—where the summer days are long and light, and the winter days short and dark—that’s changed. Now I just write when I write.

I think I made some mistakes handling my treatment of some real people in my first book: a couple things that seemed innocuous to me turned out to have been hurtful to others. Since then, I have approached writing about real people with deeper tenderness and, I hope, greater sensitivity.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

So many. Too many? Cooking. Gardening. Walking in the woods. Bird-watching. Letterpress printing, when I can. Maybe some of these are occasional helpmates to procrastination (not that I need much help in that department), but all of them support my writing in some way or other. They really do. And although some people may be skeptical about this, it is the God’s honest truth that lying on my couch, thinking and daydreaming, is absolutely part of my work as a writer.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I do have another book planned, and I’m very excited about it, and I’m determined to finish the proposal, which I’ve been working on for ages, soon. As soon as I get up from my couch and stop daydreaming.

Rosie, I love the cover of The Slow Road North. I love the idea of slow, how grief is something you climb out of, slowly. Grief can’t be rushed. Nor can writing, I’ve found. Easy, now, Rosie. You’ve earned it.

I loved the naming of daydreaming on the couch as being important to writing! And sending this piece to my mom who has been telling me for years about the book she has in her head.