I am good.

I do the right thing. I follow the rules. I speak up for others. I give the benefit of the doubt. I ask questions of people, of Google, of the future. I face down villains, demons, and cowards.

I am strong.

I lift boxes. I make my own soup when I am sick, then put myself to bed. I have a sense of humor; it grew down from the gallows.

I am good at falling pregnant, or at least I was once. It took time—days, or months, or years, depending on who’s counting—but my body did what it was told it could not.

It turns out the oldest experiment can still work: my egg gave, and his sperm entered. No miracle, just science.

My first and only pregnancy happened during a pandemic, and from behind masks and through screens, I listened to those who knew much more than I about the business of growing more pregnant until months passed, and the push and pull of existence took over. My goal was that we – me, the vessel; he, the creature – should survive. A low bar, perhaps, but also, in the end, the only one that matters.

Cells multiplied, and as they did, I found I was also good at deferring to doctors and those who promised they held ancient wisdom. The creature did not hurt me, even as he burrowed into my uterine lining, and I doubled over in pain. He was the light, and what I learned of myself, of doctors, of the woo-woo, became the after-birth.

A seed that lay dormant until, during my pregnancy, it wound its way through my intestines to the very edge of my skin. A primal pulsing thing born to a woman betrayed by science and history. I’ve managed to trap, behind the soft dip at the bottom of my neck, a gorgeous thing: a life-giving rage.

***

My first trimester was half over when we moved from a four-story walk-up into a three. Our new street was littered with dog shit; dead rats were nestled in the green tufts that grew in the cracks of the broken pavement. But we loved it because our living room overlooked an empty lot that was once full of junked cars, and was now filled with feral cats. We had a view – of a water tower and sunset – and a cross breeze. It was beautiful.

I decided to have an easy pregnancy. All that would change was that I would report the news during a deadly pandemic in a mask. The pregnancy decided differently. It was decidedly un-easy: cramps, nausea, then vertigo, which hit me like a strong wind, and I was a tree toppled over, my roots exposed and stretching toward the Earth, seeking nutrients.

I decided to have an easy pregnancy. All that would change was that I would report the news during a deadly pandemic in a mask. The pregnancy decided differently. It was decidedly un-easy: cramps, nausea, then vertigo, which hit me like a strong wind, and I was a tree toppled over, my roots exposed and stretching toward the Earth, seeking nutrients.

The second trimester, people promised, would be different. I would be filled with energy. I would glow.

In my sixth month, I attended a Hostile Environment and Emergency First Aid Training. I laughed as I half-crawled along the floor, trying not to put pressure on my belly, as I play-acted, pulling my colleagues from the path of riot police and angry protesters toward safety. I wrapped a tourniquet here and staunched, splurting fake blood there. I jumped and ran. I did not acknowledge that my pelvis hurt. If I flinched, I worried someone would try to help.

A friend took a picture of me in a Kevlar PRESS vest and a helmet. In the picture, I am beaming. I am proud.

The next week, I went to the doctor, and he said the placenta had grown too close to my cervical opening. I was not required to be on bed rest, but the doctor recommended I stay in bed. There was a risk of hemorrhaging – the fetus was fine, but if I started bleeding, they might not be able to stop it. We would all be in trouble then.

So, no jumping, the doctor said.

No problem, I promised.

***

The creature was growing low, encased between my pelvic bones. Walking became an effort. I stayed in the apartment, prone on the bed. With my camera off, I clicked Meeting windows open. Day in, day out, I did not move. I half wished I had yellow wallpaper to crawl inside.

It was not just the creeping placenta and stretching bones that kept me inside: a virus was spreading with no vaccine yet to stem it. And not just that. That year, there were storms and fires, uprisings and elections. Then, a new year dawned, and in rapid succession, there was another election, an insurrection, and finally an inauguration.

The next week, I went to the doctor, and he said the placenta had grown too close to my cervical opening. I was not required to be on bed rest, but the doctor recommended I stay in bed. There was a risk of hemorrhaging – the fetus was fine, but if I started bleeding, they might not be able to stop it. We would all be in trouble then.

I stayed in our apartment and shifted uncomfortably, filing copy and staring out at the cats crisscrossing the lot along the way.

I grew larger and larger; the creature's head pushed down, hard against my cervix. My body clenched in response.

Then, towards the end of the eighth month, I filled with fluid. My blood pressure spiked. Up and up, and up it went.

The doctor called us at home.

It’s time, he said.

It was, he insisted, too dangerous for us to wait for nature to nurture the end of this gestation. I don’t think I understood what that meant, not really. Babies are born every day, after all. After all, our bodies know the score.

I remember a story someone told me about her friend who gave birth to her third child alone in the bathtub.

Oh dear God, I laughed.

Nothing to it. Your body will know what to do, people promised, forgetting perhaps how for most of human existence, our wise women’s bodies died, or killed, or were killed while doing this most radical thing.

At 10 p.m. on a Saturday, we arrived at the hospital, ready for the creature to be induced to leave the inside of me.

He’s low, a doctor said, he’s ready.

A nurse asked for the birth plan. Ours was laughably simple: I wanted to walk as I labored; I wanted skin-to-skin as soon as he came out.

I’m not interested in either of us dying, I said, laughing. But also, I said, I don’t want this to go on for days.

She wrote the plan on a whiteboard. I looked at my husband, and we took a picture; I wondered if I would feel nostalgic for the time it was just the creature and me, and we were one.

The author Mary Shelley was a teenager when she started growing, then losing her children. And she was recently post-partum when, in a great house in Switzerland, surrounded by poets, a doctor, and her sister, she had nightmares of the two-week-old baby she had just lost. In her dream, the small creature – a girl child – was cold and needed the breath of life. It was also during this trip, the famous gauntlet was thrown: write a ghost story.

As the nurse readied the pitocin, I hobbled to the bathroom, dragging the I.V. and the baby’s heart monitor with me. During this short journey, the creature turned; his heart rate plunged, and I was unaware. I looked over to see the nurse’s face turn white. She hit a button on the wall, and twenty people rushed into the room.

Nurses, midwives, doctors, and surgeons. All of them worried for the creature. They told me to stay still.

Don’t move, they said like a disjointed Greek chorus. The doctor in charge told me that I was now on bed rest. I looked over his shoulder at the birth plan. Ten minutes old and already out of date.

The nurse pushed down on the plunger; the pitocin shot into my system.

Much later, I realized that was the moment I should have asked for the operation.

***

People talk about Frankenstein.

The movies feature a green blockhead with screws in the temples or an infantile woman thirsting for an orgasm. The rise of artificial intelligence is another version of Dr. Frankenstein’s monster: a quick, enormous program learning from all of us and regurgitating a version of humanity we shrink from. A version of us that’s, at best, a draft ready for a heavy hand to be rewritten. We rarely see the author of the Beast, the creator of the creature who was abandoned by Dr. Frankenstein and left alone, squinting against the sun, trying to find his way in the world.

The author Mary Shelley was a teenager when she started growing, then losing her children. And she was recently post-partum when, in a great house in Switzerland, surrounded by poets, a doctor, and her sister, she had nightmares of the two-week-old baby she had just lost. In her dream, the small creature – a girl child – was cold and needed the breath of life. It was also during this trip, the famous gauntlet was thrown: write a ghost story.

I ask you, who better to write a ghost story than a teenager whose mother had died from an infection she had contracted during childbirth after the man-midwife arrived late on the scene? A man who went on to garner fame and acclaim off the back of his midwifery skills? Who better to write about the pain of losing your creator – your dearest teacher – than a young woman who had also recently lost her firstborn, and then who would go on to lose three of her four children?

In America, regardless of politics, people fret over the trauma of deciding to end a pregnancy while willfully ignoring the complex strangeness and pain of matrescence, the name anthropologists at least have given the process of becoming a mother.

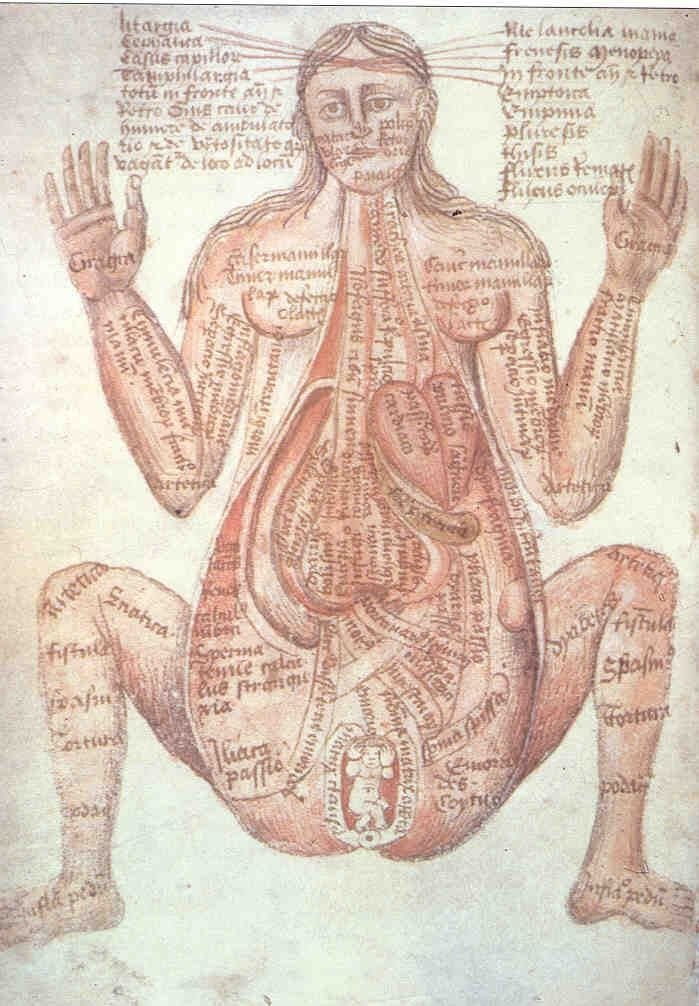

No matter how we become Mother, we are torn in the process, sometimes physically and always mentally, and then we are stitched back together. Arising from the table, we are always a new thing. This is the lesson I would learn.

Of the myriad ways to read Frankenstein, it feels most powerful as a meditation on the fear and grief of motherhood and creation. In the book, the scientist is chasing his creation through the icy Arctic, trying and failing to kill the thing he had made, which is a person stitched up from pieces, misunderstood, calling out for comfort, for love, for guidance, for knowledge, for understanding, and, most poignantly, for acceptance. The creature is the person we mothers are when we rise up from the operating table or the birthing bed. We will not, cannot, and perhaps should not be the same as we were before. Melancholy chased Mary Shelley throughout her life, like so many ghosts of those she loved and lost. But so, too, did art and the call to create.

But no matter how we become Mother, we are torn in the process, sometimes physically and always mentally, and then we are stitched back together. Arising from the table, we are always a new thing. This is the lesson I would learn.

***

Three years later, the creature thrives. The cells I grew are contained within his body. His face resembles my husband's, but his laugh is mine. Though, somehow, he, the child, is himself, uniquely. The creature tumbles into and out of my arms. His primary emotion, it seems, is joy; he only seeks knowledge and comfort.

Being his mother comes easy. It is a natural extension of the me who was not his mother. As he carries my cells within him, I carry his inside me. We are sutured together, and our togetherness is a safe harbor, a respite for the part of me that, since he was born, has grown into something new.

Such a compelling read. And an intriguing choice of illustration, which drew me in. As someone who's never had an "according to birth plan" delivery, my heart was in my mouth.

As a Brit Lit teacher who has read, re-read, and shared this story with hundreds of students, I've never felt exactly what I felt while reading this, especially the ending. It's incredible! Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter would be honored. Thank you for crafting this. ❤️