The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #40: Elissa Altman

"As someone who teaches memoir, it’s probably the biggest issue that I see: writers, almost always women, who don’t believe that they have the right to create because of secrets and shame."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

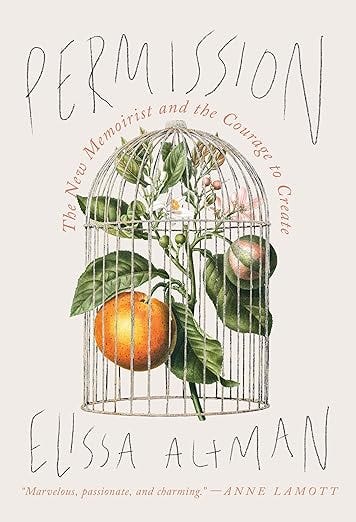

Here’s the 40th installment, featuring serial Elissa Altman author of the forthcoming Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create. -Sari Botton

is the author of the upcoming Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create (Godine Books, 2025) and the critically-acclaimed, award-winning author of three memoirs: Motherland: A Memoir of Life, Loathing, and Longing; Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw; and Poor Man’s Feast: A Love Story of Comfort, Desire, and the Art of Simple Cooking. The 2023 Barnswallow Writer-in-Residence and recipient of a 2023 Corsicana Artists and Writers Residency, Altman’s work has appeared everywhere from Bitter Southerner and Orion to The Guardian, Narrative, O: The Oprah Magazine, Lion’s Roar, Krista Tippett’s On Being, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post, where her column, Feeding My Mother, ran for a year. Creator of the acclaimed newsletter Poor Man’s Feast, Altman is a James Beard Award-winner for narrative food writing, a finalist for the 2020 Lambda Literary Award in Memoir and the 2020 Maine Literary Award in Memoir, and teaches the craft of memoir widely. She divides her time between Maine and Connecticut.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I am 60, and have been writing professionally since the mid-nineties.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create (Godine Books, early 2025)

What number book is this for you?

Permission is my fourth book (really my fifth if you include my cookbook, which came out in 2005, and which I never talk about).

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

Permission is a mix of master class and memoir. It started out life as an exploration of creative ownership, unpacking issues surrounding who does and doesn’t have the right to tell a particular story, and why, and how writers can transcend fear in order to move forward in their work. While at a residency about a year into the drafting it, I realized that I couldn’t possibly write the book without context: I had to unpack how I personally got to this place where permission to create became front and center in my writing life, and how my experience turned everything I thought I knew about writing upside down.

The practical aspects of the book are wrapped around personal narrative, and focus on the ways we can short-circuit fear and creative terror in order to write what needs to be written. I touch on issues of creative bullying, guilt, shame, motivation, and intention to ultimately ask the question: is this my story to tell? What if it conflicts with other versions? What if I make someone angry? What about privacy? Am I writing for revenge, or am I writing to achieve some sort of ambiguous clarity, and creative transcendence?

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Permission is a narrative, practical meditation meant to inspire, shepherd, support, and lead creatives in every arena through the emotional hazards and pitfalls of art-making. Written for those among us — almost always women — who have been warned about and against telling the stories that we carry, Permission will be an antidote to shame, a roadmap for every writer and artist at every level, and will empower readers to silence the voices; nurture the creative, storytelling heart; and overtake the elephant in the room that says You are not allowed to tell.

Permission is a mix of master class and memoir. It started out life as an exploration of creative ownership, unpacking issues surrounding who does and doesn’t have the right to tell a particular story, and why, and how writers can transcend fear in order to move forward in their work. While at a residency about a year into the drafting it, I realized that I couldn’t possibly write the book without context…

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

Permission was born out of creative sorrow, and an experience that absolutely no memoirist ever wants to face; it profoundly changed my relationship to the craft and how I engage with it, think about it, and teach it. When my first memoir, Poor Man’s Feast came out in 2013, I was sliced out of a broad swath of my family, to whom I had once been extraordinarily close. Three-quarters of the way through the book, in a single paragraph of about eight lines unpacking the reasons behind my father’s chronic yearning for safety and sustenance, I told the story of how my grandmother abandoned my father and aunt when he was three and she was eight, in 1926. No one knows why, for sure, and no one ever asked. She eventually returned, but the damage was done, and my father passed along to me an urgent need for security that defined much of his, and my, life.

What I did not know at the time of the writing was that while my father talked about his mother’s leaving every day of my young life — ruminating about it at breakfast and dinner and on dog-walks in the evening, in a manner I can only call obsessive; I grew up thinking that parental abandonment was not only normal but inevitable — his sister (my aunt) hid it from her grown children and grandchildren. After my book came out, several of my cousins were very much blindsided by the story. I loved these people deeply, and I regret not sharing what I was writing first, but I didn’t think I had to, because, to my knowledge, it was just an ancient story. When I was excised from my family for this supposed transgression — telling a secret that I never knew was a secret — I fell into a depression that resulted in creative paralysis. It didn’t matter that the story was almost a century old, and that all parties connected to it, except for my aunt, were long dead: my wife and I were simply cut out of the family, out of holiday meals, out of our role as godparents, out of the family plot. One of the last conversations I had with the person responsible for my excision ended with her saying We did not give you permission to tell this story. I hadn’t known that I needed it.

After I lost my family, I went through grief counseling, and it took years for me to be able to even talk about it publicly. When I finally did, it came as both a creative warning and a question: When are we allowed to tell our stories, and when are we not? What are the ethics behind telling a story about an event at which you were not present? Is it worth the risk of loss? If you are compelled by a particular situation but not directly impacted by it, is it yours to write about? Who owns the right to tell a family story? A cultural story?

The questions are far-reaching, and I came to understand that almost every one of my workshop students who had hit a creative wall had done so because, at root, they didn’t believe they had the right to tell the story at the core of their piece. In two cases, writers — one of them an award-winning novelist — were afraid of a particular family member’s response, even though that family member had died years earlier. This is where I had to unpack issues of old ghosts, of visceral prohibitions, of the power of ancient family secrets, shame, and scapegoating. I also came to the realization that the requirement of permission is almost always a woman’s issue; male writers generally don’t ask permission — they just write what they must and deal with the fallout later.

How did I become a writer? I didn’t have a choice. What’s that old Grace Paley line: I couldn’t not write any more than I could change the color of my eyes, or the sound of my voice. When I’m not writing, I get twitchy; I don’t sleep; my self-care goes out the window; I’m prone to relapse, and to drinking a lot of shitty wine. It’s been like this for decades, which is probably why when I’m nearing the end of one manuscript, I’m already starting another. I can’t let grass grow under my feet.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

I went through some significant practical issues surrounding the publication of my last book, Motherland which, while very well-received, was hobbled by a lot of speedbumps: my agent left the agency she was with when I signed with her, the first printing was so small despite a massive advance that they had to go back to press the day after publication, on and on. As a former acquisitions editor, I know exactly what can go wrong and I know when it does; I can feel the air move. I had a brilliant and wonderful editor, with whom I remain close to this day, but a few months before Covid struck, someone else connected to the book (not on the publisher’s side) told me over lunch, Your writing days are done. Two weeks later, Motherland was picked up by People Magazine and Oprah.

It’s a cautionary tale writ large: big advances can mean nothing and can even be a liability for the sale of your next book if the support for the former is disproportionate to the publisher’s investment in it. But far beyond that, my lunch date’s words stuck with me (as they were meant to) and despite all evidence to the contrary, I actually believed her and I suddenly lost all confidence, which is exactly what she wanted to happen. It was a level of cruelty and hurtfulness that was so gob-smacking that it verged on the comical. Looking back, it was like something out of Curb Your Enthusiasm.

But then we went into lockdown, my mother moved in with us for four months, and I started writing again often late into the night, this time about what it means to be told You can’t or You’re not allowed or You’ll fail or Who do you think you are. Ancient messages of fear, control, propriety, shame, manipulation: they are all part of the creative process — they will never not be — and I have seen some of the most brilliant writers put their pens down and walk away rather than grapple with them.

Four years before Covid struck, I published an essay on Krista Tippett’s On Being site that grew out of my experience losing family to something I had written; the essay was about permission to create, and permission to succeed at creating. The subject has been with me for a long time, and as someone who teaches memoir, it’s probably the biggest issue that I see: writers, almost always women, who don’t believe that they have the right to create because of secrets and shame.

I do not know any writer who doesn’t suffer from insecurity to a greater or lesser extent; creative self-loathing is just another form of permission turned upside down. Once I overcame it — a constant battle for me — I couldn’t get the horse back into the barn: the words came easily, and I knew what Permission needed to be. But I also knew that because of its hybrid nature, it was going to need a strong editorial hand. I have been extraordinary lucky to find that in an amazing literary publisher, and an agent who has stuck by it and never once wavered. But getting to this place was like orchestrating The Allied Landings.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

It depends entirely on the person and the situation. In Poor Man’s Feast and Treyf, I did change many names and identifying details, including that of my ex, who was not and is not out, and is visible in her community; in Motherland, I changed the names of two people who appear in the book. I know that some authors have a hard and fast rule about this, and some publishers do as well, but I take it on a case-by-case basis. In Permission, a key person in the book was not named at all; this person has had a tremendous amount of anguish and grief in their life, and there was no reason to name them. I am interested in fairness and clarity, not victimhood or revenge (which has its own chapter in the book). That said, I did run a section by someone who is mentioned by name in the book, because I was relating a story of theirs that happened in the early nineties and which I had heard about third hand; I wanted to get it right so I reached out to confirm it, which she appreciated. (It was about the compulsive need to write while one’s book is in process, and the lengths we will go to finish something while life and the needs of others, like our children, swirls around us.) But I haven’t shared the work with other people who appear in the book — other authors or artists who are used by example — because I didn’t feel I needed to; everything was sourced. And if something is conjecture, I say it is.

I do think that it’s important to let people know that we’re writing a book about a particular subject, especially if it’s memoir. But the blanket obligation to show it to absolutely every person who appears in it feels misguided, creatively dangerous, and often born of guilt. To quote Dani Shapiro, no one ever says Yay! There’s a memoirist in the family! A longtime student of mine — a brilliant writer who is working on her first book — felt the need to share a part of her manuscript with an ill, distant family member; she had fictionalized her story, and still, the urge was there. The section was not about the family member, but a long-dead member of his family of origin. She was nervous about showing it to him in the name of permission, so I asked her to consider these questions: how was she hoping he would respond? What was her motivation for asking him? To get his permission? If he refused to give her his blessing — even though it was fiction — would she publish it anyway, or kill the project entirely and tear up the contract?

I think that these are all fair questions, and we’re remiss if we don’t ask them of ourselves. Permission is not about giving oneself carte blanche to write whatever one wants; it is about creative and ethical responsibility, clarity, and the unpacking of truth. Which means that sometimes, one has to walk away from the thing one most wants to write about. That’s the B side to permission.

When my first memoir, Poor Man’s Feast came out in 2013, I was sliced out of a broad swath of my family, to whom I had once been extraordinarily close. Three-quarters of the way through the book, in a single paragraph of about eight lines unpacking the reasons behind my father’s chronic yearning for safety and sustenance, I told the story of how my grandmother abandoned my father and aunt when he was three and she was eight, in 1926.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

I have carried around my dog-eared, underscored copy of Janna Malamud Smith’s An Absorbing Errand for years, since reading it while traveling home from the Tin House Summer Workshop I attended almost a decade ago. Permission was beginning to take root, and I had become obsessed by the idea of story ownership and who controls the “right” to tell them. I found myself utterly compelled by Smith’s words on art-making and shame; she writes art-making transforms shame with agency, and just reading that line had an enormous effect on me. I also drew a lot of inspiration from Vivian Gornick’s The Situation and the Story, along with her Paris Review interview. One of the questions that comes up repeatedly in my workshops is how we can learn to take a giant step back and treat our narrator as a character rather than someone who is driving the team of horses, manipulating and pulling the story this way and that way. When we’re able to do this — to let go of the side of the pool, as my teacher Charlie D’Ambrosio used to say — we’re then able to allow the voice of the piece to be far more expansive and authentic. It also doesn’t allow for self-pity, woe-is-me, look-at-how-the-world-has-fucked-me victimhood. That is not what Permission is about.

Other authors who inspired me profoundly while writing Permission include Anne Lamott, Dani Shapiro, George Saunders, Claire Messud, Colum McCann, Lewis Hyde, Melissa Febos, Rick Rubin, Willa Cather, and Bonnie Friedman, whose Writing Past Dark is absolutely seminal for me.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Before plunging into it, try to understand your motivation: what is it that is driving you? What are you trying to accomplish? If you are not completely obsessed by the subject at hand, it might not be the right time to write the book. If you never become obsessed by the subject, it might never be the right time to write it. When we think about permission and story ownership, it’s imperative that we have real clarity on our own creative intentions. Are we being fair? Think about and answer these questions: Is this your story to write? Or is it just a great story but it happened to someone else? Not all stories are meant to be written, and not all stories are safe; we must truly understand not only what we’re trying to create, but why we are wanting to create it.

What do you love about writing?

Everything.

What frustrates you about writing?

Everything.

What about writing surprises you?

That my wife still loves me even when I’m in the throes of it, which is often not pretty. Otherwise, that moment, usually in the second or third draft, when a book takes on a life of its own – its own sensibility, its own voice – and becomes something other than what I had planned for it. Best laid plans: if you’re a writer, give them up.

Another surprise: the realization that writing is an absolutely, completely exhausting exercise, and it never gets easier.

A final surprise: readers always bubble to the surface who are convinced that you are writing about them, even when that couldn’t be further from the truth. At best, it doesn’t become a problem. At worst, it can be a narcissistic hellscape because people always want to believe what they want to believe, and there is usually no shaking them out of it.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

It’s taken me four books and hundreds of essays to realize that I am an afternoon writer. It’s as though I have to blow the layers of dust off my creative brain in order to get all the flies moving in the same direction. I’ve also come to understand that until a first line reveals itself to me – either in books or essays – writing is like breaking up cement bricks. The revelation usually happens when I’m doing something completely unrelated: walking, hiking, driving somewhere, playing the guitar, cooking. I always carry a small notebook with me so I don’t have to trust my increasingly shitty memory. No notebook? The voice recorder app on my phone works in a snap.

I do think that it’s important to let people know that we’re writing a book about a particular subject, especially if it’s memoir. But the blanket obligation to show it to absolutely every person who appears in it feels misguided, creatively dangerous, and often born of guilt. To quote Dani Shapiro, no one ever says Yay! There’s a memoirist in the family!

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I have played guitar for a very long time, both professionally and not; I started playing when I was four, so that’s fifty-six years ago. I was highly secretive about it for years, as though it was just a different part of my life that I didn’t want anyone to know about; I would come home from my job as an editor and play for hours at a time. I play mostly finger-style guitar, which is essentially the physical, muscular manifestation of mathematical patterning. If you asked me to tell you exactly what I’m doing on every string and in every chord, I couldn’t possibly; it becomes meditational. When I’m playing, I sort of slip into another headspace that defies definition, and it absolutely supports my writing process. I also love to cook – I went to cooking school in the late 1980s — and again, it has a meditational feel to me.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I’m at the earliest stages of research on a book about the emotional ramifications of unfulfilled musical talent across multiple generations of one family. I’m also working on a piece about grief, addiction, and religion. Finally: fiction seems to have entered my brain space.